Introduction[1]

Throughout history, certain individuals have committed crimes so heinous that their names become synonymous with evil. These killers, often hiding behind professions of trust or exploiting the vulnerabilities of those around them, have left indelible marks on the collective psyche. From doctors who went off the rails and abused their medical authority to vicious predators who took advantage of people in desperate circumstances, such as Jack the Ripper terrorising the streets of London or Dennis Nilsen preying on vulnerable men, these figures manipulated, exploited, and murdered without remorse, earning their place among history’s most notorious killers. The only two things they had in common were that they were mostly men, and their killing sprees unfolded over prolonged periods, with multiple victims targeted in succession – they were all serial murderers.

This paper explores the dark motivations and methods behind these infamous criminals, focusing on how they manipulated their environments, preyed on the vulnerable, and executed their twisted desires. Through examination of the cases of Marcel Petiot, Harold Shipman, H. H. Holmes, and many others, I have identified some common threads of exploitation, deception, and brutality that transcend time and geography. While each killer’s story is unique, their near invisibility within society as they committed unspeakable acts of violence offers chilling insights into the darkest aspects of human nature.

Looking into the cases, what I have attempted to understand is:

- the actions of these killers and why they killed

- the societal conditions that allowed them to thrive

- the psychological underpinnings of their behaviour

- the lasting impact their crimes have had on the world

What’s really worrying is the unsettling reality that these monsters often operate in plain sight, exploiting the very structures meant to protect us.

Warning: This story contains descriptive accounts of torture, abuse, violence, murder and serial deviant behaviour. If you are sensitive to this material, it might be advisable not to read any further. The story should not be shown to children or other young or impressionable readers.

CAUTION: This paper is compiled from the sources stated but has not been externally reviewed. Parts of this paper include information provided via artificial intelligence which, although checked by the author, is not always accurate or reliable. Neither we nor any third parties provide any warranty or guarantee as to the accuracy, timeliness, performance, completeness or suitability of the information and materials covered in this paper for any particular purpose. Such information and materials may contain inaccuracies or errors and we expressly exclude liability for any such inaccuracies or errors to the fullest extent permitted by law. Your use of any information or materials on this website is entirely at your own risk, for which we shall not be liable. It shall be your own responsibility to ensure that any products, services or information available through this paper meet your specific requirements and you should neither take action nor exercise inaction without taking appropriate professional advice. The hyperlinks were current at the date of publication.

Ancient Serial Killers

In ancient times, figures matching the psychological profile of a modern deviant serial killer are rare. The understanding of psychology and deviant behaviour was not as developed, and what we know today might have been obscured by myths or exaggerated accounts. There are several factors why ancient serial deviant killers, who killed for reasons other than political or military power, have remained elusive in historical records, such as:

- Cultural context: In many ancient cultures, personal and ritual killings may not have been recorded or regarded with the same moral condemnation. What is recognised today as deviant might have been interpreted through the lens of ritual, punishment, or divine sanction in earlier and ancient societies.

- Documentation: Records of individual criminal behaviour, particularly non-political murderers, were often not preserved or detailed in the same way as political or military histories.

Serial murderers are not just a modern phenomenon; there are documented cases and speculations about serial killers from ancient times, including the Roman and Greek periods. Despite the scarcity of records, there are several figures from antiquity who have been linked to patterns of serial killing:

- Apollodorus of Cassandreia (4th century BC) – Greece: Although not well-known, Apollodorus was a military leader who was described as sadistic and excessively violent. In his role as a tyrant, he reportedly took pleasure in killing many of his subjects and enemies. Ancient sources mention his cruelty and willingness to murder repeatedly, making him a candidate for early serial killer status.

- Locusta of Gaul (1st century AD) – Rome: Locusta was a notorious poisoner during the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero. Known as a professional assassin, she was implicated in several high-profile murders by poison, including those of Emperor Claudius and Britannicus, the son of Claudius and stepson of Nero. Locusta was considered a master of her craft, and while she was not a killer for personal gratification, she fits the mould of a serial killer who murdered for financial gain and influence.

- Dio of Antioch (1st century AD) – Rome: Dio was an infamous serial poisoner who targeted both high-ranking Roman officials and common people. While not as widely known as Locusta, Dio represents another figure who used murder as a method of power and profit, killing multiple people to further his own standing and influence.

- The Emperor Commodus (AD 161–192) – Rome: While not a conventional serial killer, Emperor Commodus of Rome was known for his psychopathic tendencies and bloodlust. He would routinely kill during gladiatorial games, fighting himself in the arena and executing helpless victims. His obsession with blood sport and his random acts of violence and executions contributed to a reign of terror during his time as emperor.

- Procrustes (Greek Mythology): Although a figure of legend, Procrustes fits the archetype of a sadistic serial killer. According to myth, Procrustes would lure travellers to his home, where he would stretch or amputate their limbs to make them fit an iron bed, murdering many along the way. While mythological, Procrustes’ story reflects an awareness in ancient Greece of individuals who kill repeatedly with a perverse method or ritual.

These ancient figures, whether real or mythologised, suggest that the phenomenon of serial killing—while less understood in those times—existed in various forms, from political assassinations to sadistic murders. The limited documentation, combined with ancient societies’ different views on violence, means that many cases likely went unrecorded or were interpreted from a different perspective than today.

One of the earliest documented examples of an evil, warped, and mentally damaged individual who could be classified as a serial killer is Gilles de Rais (known as Baron de Rais), a 15th century French nobleman. He is often cited as a known serial killer in European history. He was a leader in the French army during the Hundred Years’ War.

Meet Gilles de Rais

Gilles de Rais was a former companion-in-arms of Joan of Arc and a wealthy and powerful man in his time. However, beneath his aristocratic exterior, he harboured a deeply disturbed and violent personality. After his military career, he turned to the occult, seeking alchemical and magical powers, but this descent into darkness soon morphed into far more sinister and grotesque behaviour.

Between 1432 and 1440, de Rais is believed to have tortured, raped, and murdered dozens, if not hundreds, of children, mostly young boys, in the regions of Brittany, Anjou, and Poitou. His methods were cruel, sadistic, and bizarre, involving tempting the children to his castle under false pretences and subjecting them to horrifying physical and sexual abuse before eventually killing them. He seemed to derive a perverse pleasure from the suffering he inflicted on his victims, and his killings were marked by extreme cruelty and depravity, often involving elaborate rituals.

De Rais was a thoroughly disturbed and nasty person. His comeuppance arrived in 1440 when he was arrested, tried, and convicted of murder, sodomy, and heresy, after which he was sentenced to death. He was hanged and then burned at the stake, but his case left an indelible mark on history. His crimes were shocking even for a time when violence and cruelty were not uncommon, and his actions set a grim precedent for what we would today recognise as the behaviour of a serial killer.

Common Characteristics of Serial Killers

I hope this section makes things a little clearer about serial killers and who, by definition, they are. Serial killers are a distinct category of violent criminals. They differ from other murderers in their motives, psychological profiles, patterns of behaviour, and the nature of their crimes. To understand them, we must look at their traits and characteristics, as well as the key differences that set them apart from other murderers – such as mass murderers, spree killers, and those committing crimes of passion or greed.

A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is a person who murders three (although some say only two) or more people, with the killings taking place over a significant period in separate events. Their psychological gratification is the motivation for the killings, and many serial murders involve sexual contact with the victims at different points during the murder process. The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) states that the motives of serial killers can include anger, thrill-seeking, financial gain, and attention-seeking. The victims tend to have things in common, such as demographic profile, appearance, gender, or race. As a group, serial killers suffer from a variety of personality disorders. Most are often not judged as insane under the law. Although a serial killer is a distinct classification that differs from that of a mass murderer, spree killer, or contract killer, there are overlaps between them.

Psychological, behavioural, and environmental traits

Serial killers, despite their diverse backgrounds, methods, and motivations, often share several common psychological, behavioural, and environmental traits. While no single characteristic can definitively identify a serial killer, patterns emerge when examining their lives and crimes – there are common characteristics serial killers tend to have, some of which (and there are lots of them) are:

- Early Childhood Trauma: Many serial killers experienced significant trauma during their childhood, which could include physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, neglect, or abandonment. These early experiences can severely affect the development of empathy, emotional regulation, and socialisation. Some, like Albert Fish or Ed Gein[2], suffered from extreme parental control or abuse, which contributed to their later violent tendencies. Trauma, especially when combined with other factors, may distort a child’s perception of the world, and they may learn to associate power, violence, and control with emotional satisfaction.

- Lack of Empathy and Remorse: One of the defining characteristics of many serial killers is their lack of empathy, or what is often described as a “cold, remorseless” nature. This trait is associated with psychopathy, a personality disorder that is characterised by superficial charm, a lack of guilt or remorse, and a tendency toward manipulative behaviour. Individuals like Ted Bundy exhibited these traits, often appearing charming and normal to the outside world while hiding a deeply disturbed psyche. This lack of empathy allows serial killers to commit heinous acts without feeling the emotional consequences that most people would experience.

- Sadistic and Violent Fantasies: Many serial killers develop violent, sadistic fantasies long before they commit their first murder. These fantasies often involve power, dominance, and control over others, frequently involving sexual violence. The fantasy becomes a way for them to exert control, and as the fantasy becomes more intense, it eventually demands physical manifestation. Ted Bundy, for example, admitted that he began fantasising about sexual violence in his teenage years, and as time went on, these fantasies escalated until they culminated in actual murders.

- Gradual Escalation: Most serial killers don’t start with murder. Their violent tendencies often escalate over time, beginning with lesser crimes such as theft, arson, animal cruelty, or sexual assault. This gradual escalation allows them to test boundaries, refine their methods, and build confidence. Jeffrey Dahmer, for instance, exhibited signs of cruelty to animals and socially deviant behaviour long before he started killing humans. Escalation provides a serial killer with a sense of control and the ability to practice their violent urges before fully acting on them.

- Paraphilias and Sexual Deviance: A significant number of serial killers have deviant sexual fantasies or engage in paraphilic behaviours, which involve abnormal sexual desires that are harmful or distressing to others. These can range from necrophilia, as seen in the case of Edmund Kemper[3], to sexual sadism, as exhibited by Richard Ramirez[4]. Often, these killers are sexually aroused by inflicting pain, suffering, or even death upon their victims, and the murder itself becomes a part of their sexual release.

- Desire for Power and Control: Many serial killers are driven by a need for power and control over their victims. This compulsion is often tied to feelings of inadequacy, impotence, or helplessness in other aspects of their lives. The act of murder allows them to assert dominance over another person, fulfilling a psychological need for control. For instance, Dennis Rader[5], also known as the BTK Killer (Bind, Torture, Kill), was motivated by a deep desire for power over his victims, which he achieved through acts of binding and torturing them before killing them.

- Double Lives: Many serial killers are adept at leading double lives. They often appear perfectly normal to their friends, families, and co-workers, concealing their darker impulses behind a façade of normalcy. They may hold jobs, maintain relationships, and participate in social activities, making it difficult for those around them to suspect their involvement in such heinous acts. John Wayne Gacy[6], for example, was a successful businessman and community figure, even dressing as a clown for children’s parties while secretly committing brutal murders.

- ‘Stalking’ Behaviour: Serial killers often exhibit a hunting behaviour similar to predators in the animal kingdom. They carefully select their victims based on specific traits, such as vulnerability, appearance, or accessibility. Some, like Jack the Ripper, targeted women in impoverished areas, while others, like Jeffrey Dahmer, preyed on young men. Serial killers often develop specific “victim types” based on personal preferences or fantasies, and they may spend considerable time stalking or grooming their victims before striking.

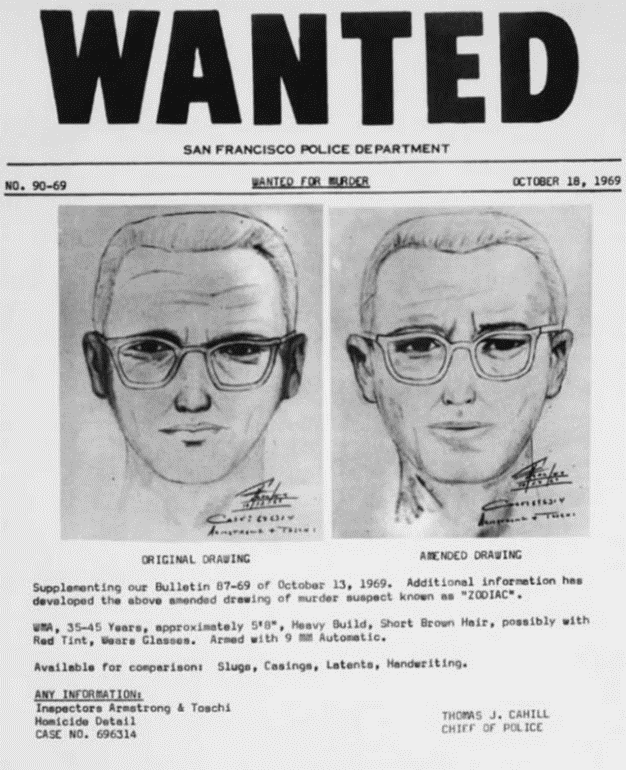

- Compulsion and Ritual: For many serial killers, murder becomes a compulsion—a repetitive act that they feel driven to commit over and over again. This compulsion often involves specific rituals or behaviours that are part of their psychological need for control. Some killers, like the Zodiac Killer, would leave taunting messages or cryptic clues, while others, like Ed Gein, would engage in bizarre rituals involving their victims’ bodies, turning them into macabre trophies. The ritualistic aspect of serial killing serves to heighten the killer’s sense of power and control, making each act of murder an extension of their internal fantasies.

- Trigger Events: Many serial killers cite specific “trigger events” that forced them over the edge from fantasy into reality. These could be traumatic events, personal crises, or failures that cause them to act on their violent impulses. These triggers often provoke feelings of anger, frustration, or desperation, which the killer channels into violence. For instance, Ted Bundy claimed that the end of a romantic relationship played a significant role in his first murder spree.

- Difficulty in Social Relationships: Serial killers often struggle to form meaningful, healthy relationships with others. They may be loners, socially awkward, or display antisocial tendencies. Their inability to empathise with others can make it difficult for them to connect emotionally. While some, like Bundy or Gacy, were able to feign charm and normalcy to manipulate others, most serial killers fail to maintain long-term friendships, marriages, or other social bonds due to their pathological behaviour.

- Mental Illness: Many serial killers suffer from mental illnesses, particularly personality disorders such as psychopathy, narcissistic personality disorder, or antisocial personality disorder. These conditions can affect their ability to experience empathy, guilt, or remorse, which allows them to kill without the emotional consequences that would affect most people. Some, like Ed Gein, exhibited signs of schizophrenia, while others, like Richard Ramirez, showed clear signs of psychopathy. Although mental illness alone does not make someone a serial killer, it can exacerbate violent tendencies, particularly when combined with other factors like trauma and deviant fantasies.

- Confidence and Arrogance: As serial killers continue to evade capture, they often become more confident and arrogant, believing that they are too smart to be caught. This sense of invincibility can lead to increasingly brazen behaviour, such as taunting law enforcement or taking greater risks during their murders. The Zodiac Killer and Dennis Rader both famously taunted the police and the media, confident that their identities would remain hidden.

- Collection of Trophies or Souvenirs: Many serial killers keep “trophies” from their victims as a way of reliving their crimes. These items can range from personal belongings like jewellery and clothing to body parts or photographs. Keeping trophies allows the killer to revisit the emotional high of the murder and serves as a reminder of their power over their victims. For example, Edmund Kemper would take photographs of his victims’ bodies after killing them, while Jeffrey Dahmer kept the skulls and bones of his victims as macabre souvenirs.

These characteristics highlight the complexity and variation among serial killers while also revealing the dark patterns that often emerge in their behaviours. Understanding these traits is crucial for criminologists, psychologists, and law enforcement in identifying and capturing serial offenders before they can claim more victims. However, it’s essential to remember that no single factor can explain or predict serial killing, as these crimes are often the result of a complex interplay of psychological, social, and environmental factors.

Serial Killers: Differences from Other Types of Murderers

- Mass Murderers: Mass murderers, unlike serial killers, commit multiple murders in a single event. These murders are often carried out in a specific location, such as a school, workplace, or public space, and the event typically ends with the murderer’s capture or death. The motive behind mass murderers is often tied to personal grievances, revenge, or a desire to make a statement. For example, mass shootings in schools or workplaces are often carried out by individuals who feel wronged by society, their peers, or an institution. Unlike serial killers, who kill for prolonged psychological gratification, mass murderers often act impulsively or as a final, desperate attempt to assert control or make a point.

- Spree Killers: Spree killers commit multiple murders in a short period, often moving from one location to another. There is no cooling-off period between the murders, which is a key difference from serial killers. Spree killers are driven by intense emotions like anger, desperation, or fear, and their crimes are usually triggered by a specific event. For instance, spree killings might occur in the context of a crime spree (such as a robbery) or an escape from law enforcement. The lack of planning, repetitive rituals, and cooling-off periods distinguishes spree killers from serial killers, whose crimes are more calculated and extend over a longer time.

- Crimes of Passion: Murderers who commit crimes of passion are typically driven by intense emotional responses to a specific situation. These murders are often impulsive and occur in the heat of the moment, such as during a domestic dispute or in reaction to betrayal. In contrast, serial killers premeditate their crimes and are driven by internal psychological needs rather than immediate emotional triggers. Crimes of passion usually involve people who know each other, whereas serial killers frequently target strangers who fit their fantasy-driven profile.

- Contract Killers: Contract killers or hitmen differ significantly from serial killers in terms of motivation. Their murders are not driven by psychological gratification but by external incentives such as financial gain or fulfilling someone else’s agenda. Contract killers typically do not select their victims based on personal fantasies, and they lack the emotional involvement often present in other types of murders. They carry out killings professionally and dispassionately, with the goal of completing a transaction, whereas serial killers are usually emotionally invested in the act of murder itself.

Serial killers exhibit a distinct set of characteristics that differentiate them from other types of murderers. Their motives are deeply psychological, often revolving around power, control, and the fulfilment of violent fantasies. Their crimes are repetitive and ritualistic and involve a cooling-off period, allowing them to evade detection for long periods. In contrast, other murderers, such as mass, spree, and contract killers, are driven by more situational or external factors, and their actions are typically less calculated and methodical. Serial killers’ ability to hide their deviant nature behind a façade of normalcy and manipulate their victims makes them uniquely dangerous among violent offenders. Understanding these differences is crucial for law enforcement and forensic experts in profiling, investigating, and ultimately apprehending serial killers.

Greed

Greed is a significant motive for murder, and it can be considered a distinct category of its own. While many serial killers are driven by psychological gratification, such as power, control, or sexual desires, there are also those who kill for material gain. This could include money, property, life insurance payouts, or even to cover up financial fraud. Here’s how greed fits into the broader spectrum of murder:

Greed-based murders often involve premeditated acts where the primary motivation is to gain financially or materially. This type of crime can be carried out by a wide range of killers, including:

- Serial Killers: Some serial killers are driven primarily by greed, though it might not be their sole motivation. For instance, H. H. Holmes, known for building his “Murder Castle,” often killed for financial gain, particularly by collecting life insurance money or robbing his victims.

- Contract Killers: Contract killers, or hitmen, are often motivated by greed, as they murder for financial compensation. Their killings are typically cold and calculated, lacking any personal attachment to the victims.

- Spouses or Relatives: Murders for life insurance payouts or inheritance fall under this category. For example, some people murder their spouse, family member, or business partner to inherit money or assets.

- White-Collar Criminals: In some cases, individuals involved in large-scale fraud or embezzlement may murder to cover up their financial crimes. They might eliminate someone who could expose them or who stands in the way of their financial goals.

How Greed-Driven Murder Differs from Serial Killers’ Motivations

While greed can drive both single and multiple murders, it differs significantly from the motivations typically associated with serial killers, who are often motivated by psychological impulses rather than direct financial gain. Here’s how the motives contrast:

- Greed vs. Psychological Gratification: Greed-driven murders are calculated and often transactional, where the goal is a tangible reward like money, property, or status. Serial killers, on the other hand, derive psychological pleasure from their crimes, seeking emotional or sexual fulfilment rather than financial benefit.

- Single Event vs. Repetitive Patterns: Greed-based murderers might commit a single act or a small number of killings as part of a financial scheme, whereas serial killers often operate over a long period with a repetitive pattern, driven by their internal fantasies and desires rather than financial motives.

- Connection to the Victim: Greed-driven murders often involve a personal connection between the murderer and the victim, such as a spouse, family member, or business partner. Serial killers, however, frequently target strangers who fit a particular psychological profile.

Notable Examples

Several infamous criminals have murdered for greed, including:

- H. H. Holmes: Known as America’s first documented serial killer, Holmes often murdered for financial gain, collecting life insurance payouts and robbing his victims. Although he exhibited psychological gratification in his murders, greed was a significant driving force behind many of his crimes.

- Dorothea Puente[7]: Puente operated a boarding house and murdered elderly tenants to cash their social security money. Her murders were entirely financially motivated.

- The Menendez Brothers[8]: Lyle and Erik Menendez murdered their wealthy parents in 1989 in hopes of inheriting their substantial estate. Greed was the primary motivator in this case.

Greed is a common motive for murder, and it fits into a broader understanding of why people commit murder. While serial killers are typically driven by psychological needs, some do kill for financial gain. These greed-driven murders highlight a more calculated, transactional approach to homicide, distinct from the emotionally or psychologically driven actions of many serial killers.

There now follows a profile of several serial killers.

Jack the Ripper: The Whitechapel Murderer

Jack the Ripper remains one of the most infamous and elusive serial killers in history, known for a series of brutal murders that occurred in the Whitechapel district of London’s East End in 1888. The Ripper, whose real identity was never discovered, was responsible for the gruesome killings of at least five women—often referred to as the “canonical five.” His victims were typically poor, vulnerable women, many of whom were engaged in sex work. Jack the Ripper earned his chilling nickname from a letter sent to the police at the time, although the authenticity of the letter remains disputed. He was also referred to as “The Whitechapel Murderer” due to the specific area where he operated. The mystery of his identity and the horrifying nature of his crimes have cemented his place in criminal history.

The Setting: Whitechapel and the East End of London

During the late 19th century, Whitechapel was one of the most impoverished and overcrowded areas of London. It was a grim district characterised by extreme poverty, crime, and squalid living conditions. The East End had become a haven for immigrants, particularly Eastern European Jews fleeing pogroms and persecution in their home countries.

Many of the residents lived in dire poverty, crammed into overcrowded tenements, often without access to basic sanitation or clean water. The narrow, winding streets of Whitechapel were filled with filth and plagued by disease, creating a sense of hopelessness among the people who lived there.

The desperate circumstances in the East End contributed to a high level of social dislocation. Crime, alcoholism, and violence were common, and many women, facing few options for employment, turned to prostitution to survive. In this environment, Jack the Ripper found a perfect hunting ground. The transient nature of life in Whitechapel meant that his victims were often unnoticed or forgotten, making it easier for him to operate undetected. The police, ill-equipped to handle such horrific crimes in a densely populated and chaotic area, struggled to maintain order and investigate the murders effectively.

The Ripper’s Method and Suspected Medical Knowledge

Jack the Ripper’s murders were defined by their savagery and the precise manner in which the bodies were mutilated. His victims were often found with their throats slashed and their bodies horrifically disfigured. The Ripper would remove internal organs such as the uterus and kidneys, leading many to believe that he had some degree of medical training or anatomical knowledge. Surgeons and doctors of the time speculated that the killer might have been a butcher, physician, or someone with experience in dissection, given the precision of the incisions. This theory added to the aura of fear surrounding the killer, as it suggested a person of education and skill who could move through society unnoticed while committing these brutal acts.

The police were baffled by the murders, and despite an extensive investigation, they were unable to catch the killer. Letters purportedly from the Ripper—such as the infamous “Dear Boss” letter—mocked the authorities and heightened public fear.

The killer’s ability to evade capture, despite leaving behind such gruesome crime scenes, only added to the belief that he possessed a high level of intelligence and cunning. The possibility that he had medical knowledge further terrified the public, as it suggested that he could be hiding in plain sight, potentially even among the more respectable classes of society.

Social Impact and the Horrors of Whitechapel

The Ripper’s reign of terror, though brief, had a profound impact on London society, particularly on the way the public viewed the East End. The horrific nature of his crimes and the fact that they took place in one of London’s most impoverished districts brought attention to the appalling living conditions of Whitechapel. The murders highlighted the stark contrast between the wealth of London’s West End and the abject, desperate poverty of the East End, where overcrowded slums, poor sanitation, and high crime rates were the norm.

The widespread press coverage of the murders not only shocked the Victorian public but also led to increased calls for social reform. The slums of Whitechapel became a symbol of the broader failures of the British government to address the issues of poverty and inequality. The attention generated by the murders helped to spur efforts to improve housing and sanitation in the East End. Although the Ripper’s identity was never uncovered, his legacy inadvertently drew attention to the need for social change.

The Housing Crisis and Reform

In the aftermath of the Ripper murders, there was a growing recognition that the conditions in which the residents of Whitechapel lived were untenable. Housing reform became a central issue, with philanthropists and social reformers turning their attention to the slums. One of the most significant responses to the crisis was the establishment of the Rothschild Dwellings, part of the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company founded by philanthropists, including members of the Rothschild family. These housing projects aimed to provide better living conditions for Jewish immigrants and the working-class poor, offering affordable, sanitary housing as an alternative to the squalid tenements that had defined the area.

Rothschild House and similar developments were designed to improve the health and well-being of working-class residents by offering cleaner, safer environments. These projects were part of a broader effort to address the root causes of the deprivation that had plagued the East End for so long. The murders, though horrific, catalysed change for the better by exposing the depths of the suffering in Whitechapel and forcing the government and society to deal with the neglect of its poorest citizens.

The Enduring Mystery and Legacy

Despite the massive police investigation and the involvement of prominent figures such as Sir Charles Warren, the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Jack the Ripper was never caught. Theories about his identity have ranged from members of the British aristocracy to prominent doctors and even artists like Walter Sickert. Over the years, the Ripper’s legend has only grown, with countless books, films, and documentaries speculating on his identity and motivations. The mystery surrounding his crimes has ensured that Jack the Ripper remains a figure of both horror and fascination.

The murders themselves may have been confined to a few terrifying months in 1888, but their legacy endures. They not only marked a turning point in the history of criminal investigation but also exposed the deep social divisions in Victorian London. The public outcry following the Ripper’s killings helped to galvanise efforts to improve living conditions in the East End, leading to reforms that would ultimately reshape the area. While Jack the Ripper remains one of the most notorious figures in history, his murders also inadvertently contributed to much-needed social progress.

Jack the Ripper’s terrifying reign of violence left an indelible mark on the history of London. His ability to kill with impunity in the chaotic, overcrowded streets of Whitechapel, combined with his possible medical expertise, made him a figure of enduring fear and mystery. Yet, the exposure of the horrific conditions in which his victims lived helped to initiate important social reforms.

The housing and sanitary improvements that followed in the wake of his crimes, such as Rothschild Buildings and the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings, were a direct response to the public’s newfound awareness of the plight of the East End’s poorest residents. In this way, the Ripper’s legacy is twofold—while he represents the darkest aspects of human nature, his actions also shone a light on the need for compassion, reform, and justice for society’s most vulnerable.

Dennis Nilsen: The Muswell Hill Murderer

Dennis Andrew Nilsen (1945–2018) was a Scottish serial killer and necrophile who murdered at least twelve young men and boys between 1978 and 1983 in North London. Nilsen tricked his victims—many of whom were homeless, runaways, or otherwise vulnerable—into going back to where he lived, promising them food, shelter, or companionship. Once there, he would strangle or drown them before engaging in bizarre rituals, including bathing and dressing the corpses, which he kept for extended periods before eventually dismembering them. The discovery of human remains clogging the drains at his Muswell Hill residence led to his arrest in 1983 and the uncovering of his gruesome murders.

Nilsen’s Early Life and Descent into Murder

Nilsen was born in Fraserburgh, Scotland, in 1945 to a troubled family, where he developed a strong attachment to his grandfather. The death of his grandfather when Nilsen was just five years old is thought to have had a profound effect on him. The early experience of death and viewing his grandfather’s body may have fuelled the disturbing fantasies that would later manifest in his crimes. Nilsen grew up a quiet, withdrawn boy who struggled with his sexual identity, eventually joining the British Army as a means of escape from his small-town life. After his military service, Nilsen moved to London and began working as a civil servant.

Nilsen’s sexual orientation, which he kept hidden for many years, played a role in the development of his fantasies. He longed for passive sexual partners who would not resist or abandon him, which he would later find in the form of the lifeless bodies of his victims. His crimes started in 1978 when he invited a young boy back to his apartment. After the boy fell asleep, Nilsen, afraid of being abandoned, strangled him. This marked the beginning of a five-year killing spree.

Modus Operandi and Rituals

All of Nilsen’s murders took place at two North London addresses—195 Melrose Avenue in Cricklewood and 23 Cranley Gardens in Muswell Hill. He tempted his victims—often young men struggling with homelessness or poverty—into his homes by offering them alcohol, food, or a place to stay.

Nilsen would strangle his victims, sometimes drown them to ensure they were dead, and then perform elaborate rituals on their bodies. He would wash, dress, and position the corpses, often keeping them for days or even weeks. During this time, Nilsen would engage in conversations with the bodies as if they were still alive, even watching television beside them. These rituals seemed to fulfil Nilsen’s twisted need for companionship and control.

Once the bodies began to decompose, Nilsen would dismember them, meticulously cutting the flesh from the bones and disposing of the remains either by burning them on a bonfire or flushing them down the toilet. His later victims’ remains were discovered when a plumber was called to address blocked drains at Cranley Gardens. Nilsen’s attempt to dispose of body parts through the plumbing system ultimately led to his capture.

The Horrors of 1970s and 1980s North London

During the period of Nilsen’s murders, North London, particularly in the areas where Nilsen operated, was home to a significant number of vulnerable people. Many of his victims were young men who had fallen through the cracks of society—homeless, unemployed, or transient individuals with little support. Nilsen’s ability to move through society unnoticed for so long was partly due to his choice of victims, whose disappearances often went unreported or uninvestigated for extended periods. The grim conditions in parts of London during the late 1970s and early 1980s contributed to Nilsen’s ability to carry out his horrific acts with little suspicion. The city was grappling with economic decline, rising unemployment, and a housing crisis. The lack of affordable housing and services for vulnerable populations left many individuals at risk, making them easy prey for predators like Nilsen.

Dennis Nilsen’s Time in the Police

In December 1972, after leaving the British Army, where he had served as a cook for 11 years, Nilsen decided to join the Metropolitan Police. He began his training in December of that year, and in April 1973, after completing his course, he was assigned to Willesden Green as a probationary police constable. Nilsen enjoyed the structure and discipline of police work and performed routine duties such as patrolling and making arrests.

However, his time in the police force was short-lived. He found it difficult to reconcile his personal life with his job, particularly due to his struggles with his sexuality. By August 1973, Nilsen had become increasingly disillusioned with policing and resigned from the force in December 1973, less than a year after starting. His experiences in the police force, while brief, may have contributed to his ability to avoid suspicion during his later crimes, as he had a basic understanding of investigative techniques and procedures.

Life as a Civil Servant

After leaving the police, Nilsen sought more stable employment and eventually found work as a civil servant. In May 1974, he joined the Jobcentre in Denmark Street, London, where he was responsible for helping unskilled labourers find employment. Nilsen was known to be a quiet and conscientious employee, and he became involved in union activities during his time there. Nilsen was initially content with his role as a civil servant, which offered him stability. He even received a promotion to the position of executive officer in June 1982, taking on additional supervisory responsibilities at a new location in Kentish Town. He continued working in this position until his arrest in 1983.

Despite the outward appearance of a quiet, stable civil service career, Nilsen’s personal life was deeply disturbed. He used his respectable job to maintain a facade of normalcy, which helped him to evade detection for years as he carried out his horrific murders. His professional life allowed him to blend into society and mask the monstrous acts he was committing in private, making him one of the most chilling figures in British criminal history. Nilsen’s time in both the police force and the civil service allowed him to lead a double life—publicly respectable but privately monstrous—right up until the time of his arrest.

The Impact of Nilsen’s Crimes

The discovery of Nilsen’s crimes shocked the nation. His trial at the Old Bailey in 1983 led to his conviction on six counts of murder and two counts of attempted murder, with a sentence of life imprisonment, later extended to a whole-life tariff. Unlike many other serial killers, Nilsen was unusually candid about his crimes, offering detailed confessions to the police. Yet he remained largely indifferent, claiming he had no real motive for his actions other than his desire for companionship and control over his victims.

Although Nilsen’s crimes were heinous, they did bring attention to the neglected and marginalised populations of London. His victims—many of them young, homeless, or from impoverished backgrounds—represented a broader societal failure. The conditions that allowed Nilsen to target these individuals went largely unchecked until his arrest. The horror of his actions highlighted the urgent need for improved social services, mental health care, and housing in London, much as Jack the Ripper’s murders in the late 19th century had drawn attention to the appalling conditions of the East End.

In the aftermath of Nilsen’s arrest, there was a heightened awareness of the vulnerabilities faced by homeless and at-risk young men in London. Nilsen’s crimes underscored the dangers of invisibility within society—where individuals could disappear without notice, lost within the cracks of urban life. This led to broader conversations about social safety nets, housing reform, and the protection of marginalised groups.

Dennis Nilsen’s case remains one of the most disturbing in British criminal history, not only for the sheer brutality of his acts but for the way he was able to exploit the vulnerabilities of his victims. His ability to blend into society, hiding his monstrous nature behind the facade of an ordinary civil servant, makes him a chilling figure. While his crimes drew attention to the societal neglect of vulnerable populations, they also revealed the dark, hidden currents of human nature that can exist even in the most seemingly mundane circumstances. Nilsen’s legacy serves as a stark reminder of the need for vigilance, compassion, and reform in ensuring that the most vulnerable among us are not left unprotected.

Marcel Petiot: Doctor Satan

Marcel Petiot was a greedy and unscrupulous French serial killer who murdered without remorse during World War II. He is infamous for exploiting the chaos of the war to commit a series of brutal murders under the disguise of helping people escape Nazi-occupied France. How the murders were carried out and why he committed them is a secret Dr Petiot took to his grave and remains to this day a chilling mystery.

Early Life and Background

Marcel André Henri Félix Petiot was born on 17th January 1897 in Auxerre, Yonne, France. Petiot was known to be intelligent as a child but frequently encountered difficulties in school, leading to multiple expulsions before he completed his education. At 17, he was arrested for stealing mail, but a judge later ruled him mentally unfit for trial, resulting in his release. In 1917, while serving in the French army during World War I, Petiot was brought to trial for allegedly stealing army blankets but was acquitted due to concerns about his mental health. Despite these concerns, he was sent back to the front lines, where he experienced a mental breakdown. Eventually, he was discharged from the army due to his unusual behaviour, and some medical professionals suggested that he should be institutionalised.

In 1916, during World War I, Petiot was drafted into the French Army. His military service was erratic—he was injured but also displayed erratic behaviour, leading to him being discharged for psychological reasons. He was diagnosed with mental instability, but this did not prevent him from continuing to pursue a medical career.

Medical Career and Early Criminal Activity

After the war, Petiot studied medicine in Paris, earning his degree in 1921. He started practising as a physician and built a respectable reputation. However, his darker tendencies persisted, and he became involved in various fraudulent schemes. He would prescribe narcotics freely, steal from patients, and engage in other unethical activities, although none of these early misdeeds led to serious criminal charges.

By the 1930s, Petiot had moved to Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, where he gained political office as a Mayor, no less. Financial scandals marred his tenure, and he was accused of embezzlement, leading to his eventual resignation in 1932. Afterwards, he settled in Paris, continuing his medical practice and maintaining a façade of respectability.

World War II and the Murders

During the German occupation of France in World War II, Petiot seized upon the turmoil to further his criminal enterprise. He presented himself as a hero of the French Resistance, claiming to help Jews, resistance fighters, and others in danger flee to safety in South America. He would lure victims to his clinic at 21 Rue Le Sueur in Paris with promises of escape. Instead, Petiot would murder them, steal their valuables, and dispose of their bodies.

He told his victims that they needed vaccinations for foreign travel, but he injected them with lethal doses of cyanide. After killing them, Petiot would dismember the bodies and dispose of the remains by burning them in his basement furnace or dissolving them in quicklime. He disposed of some bodies in the Seine River or buried them on his property.

Petiot’s scheme operated under the code name Dr Eugène, and it is believed he charged his victims exorbitant sums, often taking their life savings. His activities thrived during the war, as people desperately sought to escape the Nazis and trusted him due to his reputation as a physician and his claims of resistance involvement.

Discovery and Arrest

Petiot’s crimes came to light in March 1944 after neighbours complained of a foul odour and excessive smoke coming from his house. The police investigated and discovered body parts and evidence of his murders in the basement. Initially, Petiot fled and managed to evade capture for several months by adopting false identities and living under aliases. During this period, he even briefly joined the French Resistance under a pseudonym.

He was finally captured in October 1944, after the liberation of Paris, when he was recognised and arrested by French authorities. At the time of his arrest, he claimed that he had only killed collaborators and enemies of France, trying to portray himself as a patriot who had targeted German sympathisers. However, the truth soon became clear that his victims were mainly Jews and others seeking refuge from the Nazis—people he had lured with promises of safety and killed for personal gain.

Trial and Execution

Marcel Petiot’s trial began in March 1946, and it quickly became a sensational case. He was charged with 27 counts of murder, although he was suspected of having killed many more—possibly as many as 60. Petiot’s defence insisted that he was a resistance hero and that his victims were German collaborators, but the overwhelming evidence of his sadistic methods and exploitation of vulnerable people doomed him.

He was found guilty of 26 murders and sentenced to death. On 25th May 1946, Marcel Petiot was executed by guillotine in La Santé Prison in Paris. He remained defiant until the end, never admitting his guilt and portraying himself as a misunderstood patriot.

Legacy

Marcel Petiot’s case remains one of the most infamous in French criminal history. His combination of medical expertise, charisma, and ruthless exploitation of people during a time of great fear and chaos made him particularly notorious. His ability to manipulate others and evade capture for so long only added to the morbid fascination surrounding his crimes.

Although Petiot’s exact victim count is unclear, his story has become a cautionary tale of how war and social upheaval can provide cover for heinous criminal activities.

Peiot’s life and crimes have been the subject of numerous books, documentaries, and films, further cementing his place in the annals of notorious serial killers and reflecting the darker side of humanity, particularly during times of societal breakdown.

While there are similarities between Petiot and these other figures—particularly in their exploitation of vulnerable people and abuse of positions of trust—Petiot’s case remains particularly unique due to the historical context in which he operated. His ability to exploit the chaos of Nazi-occupied France and his manipulation of wartime fears to carry out his murderous schemes distinguish him from many other serial killers, whose crimes were often less directly connected to political or wartime circumstances.

In comparison to most serial killers, Petiot stands out due to his audacity in masquerading as a hero of the Resistance and using the horrors of war as a cover for personal gain. Though figures like Shipman and Holmes also abused their positions as doctors, and killers like Mengele and Clauberg took advantage of the wartime chaos to commit atrocities, Petiot’s blend of charisma, medical knowledge, and exploitation of the particular historical moment in occupied France gives him a distinct place in the history of criminal infamy.

Peter Kürten: The Vampire of Düsseldorf

Peter Kürten was one of the most notorious and terrifying serial killers in early 20th century Germany. Born on 26th May 1883, in Mülheim am Rhein, a district of Cologne, Kürten’s life was marked by extreme violence and depravity. His horrific crimes between 1929 and 1930, involving murder, sexual assault, and sadistic mutilation, earned him his nickname and made him a figure of morbid fascination and fear in German criminal history. He was ultimately captured and executed, but the legacy of his crimes continues to fascinate criminologists and psychologists.

Early Life and Upbringing

Peter Kürten’s childhood was deeply troubled and violent, shaping much of his later life. He grew up in a large, poverty-stricken family with 13 siblings. His father was an abusive alcoholic who frequently beat his wife and children. Kürten witnessed his father sexually assault his mother and sisters, which left an indelible mark on him. As a young boy, Kürten displayed violent tendencies, engaging in petty crimes and cruelty to animals, which are often early indicators of psychopathy and deep-rooted emotional disturbance.

At the age of nine, Kürten allegedly committed his first murders by drowning two of his playmates, though this claim remains unconfirmed. However, it does point to the early manifestation of his violent behaviour, which escalated over time. His exposure to violence at home, compounded by neglect and abuse, fostered an environment where such horrific tendencies could take root. Kürten’s interactions with the criminal justice system began early in life, as he was frequently arrested for theft and other petty crimes.

The Path to Murder

As Kürten grew older, his crimes became more serious. By his late teens and early twenties, he was frequently imprisoned for various offences, including arson and attempted murder. It was during these stints in prison that Kürten began to develop violent fantasies, which would later culminate in his reign of terror over Düsseldorf.

In 1913, Kürten committed his first confirmed murder when he broke into a tavern in Mülheim, intending to rob it. There, he found a nine-year-old girl named Christine Klein asleep. He strangled her and then slit her throat, drinking her blood—a disturbing detail that would later earn him his infamous moniker. Afterwards, Kürten claimed he felt a sexual thrill from the act, marking the beginning of his association of sexual gratification with violence and death.

Despite the heinous nature of this crime, Kürten managed to evade capture for several years. He served time in prison for other offences, and it wasn’t until much later that this murder was tied to him. During his incarceration, Kürten honed his fantasies of domination, sadism, and murder, further entrenching his psychopathic tendencies. Upon his release, he moved to Düsseldorf, where he married in an effort to appear normal and rejoin society, but his dark desires soon resurfaced.

The Düsseldorf Murders: 1929-1930

Kürten’s most notorious crimes took place between 1929 and 1930, during a period that became known as the Düsseldorf Horror. The crimes were shocking not only for their brutality but also for their randomness. Kürten did not have a specific type of victim. He attacked men, women, and children of all ages, often using a variety of weapons, including knives, scissors, and hammers. His methods were equally varied; he bludgeoned, stabbed, strangled, and mutilated his victims, sometimes drinking their blood afterwards, which earned him the nickname The Vampire of Düsseldorf.

The first major attack in Düsseldorf occurred on 3rd February 1929, when Kürten stabbed an elderly woman with a pair of scissors. He would go on to commit a series of violent acts that escalated in ferocity. On 8th August 1929, he stabbed a woman 24 times with a pair of scissors before leaving her for dead. Amazingly, she survived and was able to provide police with a description, though it would still be some time before Kürten was apprehended.

Later that month, Kürten bludgeoned two young girls, aged five and 14, to death. One of the bodies was found on the banks of the Rhine River, mutilated in a manner so grotesque that it shocked the nation. Kürten’s random selection of victims and the varying degrees of violence he inflicted made it difficult for authorities to track him. He seemed to strike without motive, except for the sheer pleasure he derived from killing. His ability to disappear after each attack baffled law enforcement, while his increasingly bizarre and sadistic behaviour terrified the public.

In September 1929, Kürten committed a series of brutal attacks in a single evening. First, he killed a servant girl by bludgeoning her with a hammer. He then stabbed a young girl to death and followed that by attacking a man, though the man survived. These acts of violence, all committed in a single night, highlighted Kürten’s growing boldness and the depth of his depravity. By this point, police in Düsseldorf were frantically trying to catch the killer, but Kürten’s ability to blend in with the community, combined with his intelligence and cunning, made him difficult to identify.

Kürten taunted the police by writing letters to newspapers, detailing the locations of some of the bodies he had disposed of. This brazen act of defiance added to the public fear, as it became clear that the killer was not only skilled at evading capture but was also playing a cruel game with authorities.

Capture and Trial

In May 1930, Kürten’s reign of terror came to an end when one of his victims, a young woman named Maria Budlick, managed to escape and report the attack to the police. Kürten had tempted her to his home under the pretence of helping her find lodgings, but once there, he attempted to strangle her. Budlick fought back and managed to flee, going directly to the authorities.

When Kürten’s wife learned of the attack, she suspected her husband might be the Düsseldorf murderer. She confronted him, and Kürten shockingly confessed to his crimes, detailing the extent of his murders and sadistic acts. Remarkably, Kürten willingly went with his wife to the police station and turned himself in. He later claimed that he derived great satisfaction from the thought of his execution.

Kürten’s trial began in April 1931 and was widely covered by the media. He was charged with nine murders and seven attempted murders, though he confessed to many more killings. During the trial, Kürten remained calm and composed, describing his crimes in chilling detail. He admitted to deriving sexual pleasure from the acts of murder and blood-drinking, stating that the sight of blood excited him. His trial fascinated the public, not just because of the nature of his crimes but because of his calculated demeanour, which contrasted sharply with the sadistic violence he committed.

Psychiatrists evaluated Kürten and diagnosed him with antisocial personality disorder and sadistic tendencies, but they found him sane and fully aware of his actions. Kürten showed no remorse during his trial, further shocking the public. He was convicted and sentenced to death on 22nd July 1931.

Execution and Legacy

Peter Kürten was executed by guillotine on 2nd July 1931 in Cologne, Germany. His final words were reportedly a macabre reflection of his morbid curiosity about death. He asked the executioner whether he would still be able to hear and see for a few moments after his head was severed. This question, along with the details of his horrific crimes, solidified his reputation as a monster who found pleasure in death and suffering.

After his execution, Kürten’s brain was removed and studied by scientists who hoped to find a physiological explanation for his extreme behaviour. His brain is still preserved today in the Witt Museum in Germany, serving as a chilling reminder of the depths of human depravity.

Kürten’s case remains one of the most studied in criminology, particularly because of the complex interplay between his abusive upbringing, his sexual sadism, and his psychopathic behaviour. His ability to evade detection for so long, coupled with his public persona of a mild-mannered man, makes him a classic example of the “organised” serial killer who blends into society. His case also raised questions about the nature of evil and the extent to which childhood trauma, mental illness, and environmental factors contribute to violent behaviour.

Reflection

Peter Kürten, the Vampire of Düsseldorf, was a sadistic and calculated serial killer whose reign of terror left a permanent scar on the psyche of early 20th century Germany. His crimes, which involved extreme violence, mutilation, and blood-drinking, shocked the public and confounded the police. Despite his horrific acts, Kürten managed to evade capture for years due to his ability to blend into society and his cunning nature. His trial and execution marked the end of one of the most terrifying chapters in German criminal history. Kürten remains a figure of fascination, both for his extraordinary cruelty and the psychological complexities that drove his sadistic behaviour.

Harold Shipman: Dr Death

Doctor Harold Frederick Shipman was a British general practitioner (GP) who became one of the most prolific serial killers in modern history. Born on 14th January 1946 in Nottingham, Shipman was convicted in 2000 of murdering 15 of his patients, but the true number of victims is estimated to be between 200 and 250. Throughout his medical career, Shipman used his trusted position as a doctor to secretly kill patients—most of them elderly women—by administering lethal doses of diamorphine (heroin). His case shocked the world, not only due to the sheer number of victims but also because of the manner in which he abused the immense trust placed in doctors by their patients and communities. His crimes raised serious questions about medical oversight and patient safety, sparking reforms in Britain’s healthcare system.

Early Life and Education

Harold Shipman was born into a working-class family in Nottingham and was the middle child of Vera and Harold Frederick Shipman, a lorry driver. His mother, Vera, was the dominant figure in his life and heavily influenced him as a child. Known for being somewhat cold and distant, Vera instilled in her son a sense of superiority and detachment from others. She died of lung cancer when Shipman was 17 years old, an event that had a profound impact on him.

While his mother was dying, she was given morphine to ease her pain. This experience of watching the powerful effects of morphine on his mother’s suffering is believed to have been a formative moment for Shipman. It is speculated that this early experience with the drug may have influenced his later methods of killing. Shipman’s desire to gain control over life and death—likely rooted in this period of his life—was to become a grim hallmark of his criminal career.

Shipman attended Leeds School of Medicine and graduated in 1970, entering the medical profession as a young man with good prospects. He married Primrose Oxtoby in 1966, and they had four children. From all outward appearances, Shipman seemed to be a devoted family man and an ambitious doctor. He began his career in the town of Pontefract in West Yorkshire before moving to Todmorden, a town in Lancashire, where he joined a medical practice.

Early Career and Initial Criminal Activity

Shipman’s career was not without its early troubles. In 1975, he was caught forging prescriptions for the powerful painkiller pethidine, which he had become addicted to. He was fined £600 and briefly attended a rehabilitation clinic. However, Shipman was able to return to practice medicine after this incident, a decision that would later prove catastrophic for hundreds of patients. After this disciplinary blip, Shipman appeared to rehabilitate his professional reputation and continued to work as a GP without raising further suspicions for many years.

In 1977, he moved with his family to Hyde, a small town in Greater Manchester, where he joined the Donneybrook Medical Centre. He became well-regarded by his patients and colleagues, often praised for his diligent care and manner. He was known for being reliable, punctual, and thorough. Many of his patients considered him to be a dedicated and compassionate doctor. This level of trust would ultimately allow Shipman to carry out his crimes unnoticed for nearly two decades.

Methodology

Harold Shipman’s modus operandi was both simple and chilling. He preyed primarily on older women, who trusted him as their doctor, believing he had their best interests at heart. Using his access to powerful narcotics, Shipman would administer lethal doses of diamorphine under the guise of medical treatment. Often, he would fabricate medical conditions or claim that the patient’s death was inevitable due to old age or underlying health issues.

In many cases, Shipman would call on his elderly patients at their homes or have them visit him at his surgery, administer the lethal injection, and watch as they died. One of the reasons Shipman was able to continue his killing spree undetected for such a long time was the age of his victims, who were in declining health. Most of his patients were elderly, and their deaths were often attributed to natural causes such as heart failure or other age-related conditions. Given the seemingly natural circumstances of their deaths, forensic examinations and post-mortem investigations were usually not conducted, especially since Shipman was the attending physician and could certify the cause of death himself. This lack of scrutiny allowed Shipman to continue his murders without raising suspicion, as no one thought to question the sudden deaths of patients who were believed to be nearing the end of their lives due to natural decline.

It wasn’t until the exhumation of Kathleen Grundy—whose death Shipman had certified as being from natural causes—that authorities discovered the traces of lethal diamorphine, prompting a deeper investigation into Shipman’s patient records and the high death rate among his elderly patients. One of Shipman’s most disturbing behaviours was his habit of staying with his victims as they died, sometimes chatting with them or their families, appearing entirely normal and compassionate as they passed away from the lethal dose he had administered. The sheer audacity and cold-bloodedness of this act made his crimes all the more terrifying. He managed to deflect any blame or suspicion due to the immense trust placed in doctors and his apparently impeccable reputation.

Discovery of the Crimes

Harold Shipman’s downfall began with the death of Kathleen Grundy, a wealthy 81-year-old widow and former lady mayor of Hyde. Grundy was found dead in her home in June 1998, just hours after Shipman had visited her. Her death was initially thought to be from natural causes, and Shipman had written her death certificate. However, suspicion was raised when Grundy’s daughter, Angela Woodruff, a lawyer, discovered that her mother’s will had been altered to leave nearly £400,000 to Shipman. Woodruff knew her mother would never have written such a will and reported her concerns to the police.

Grundy’s body was exhumed, and a post-mortem examination revealed traces of diamorphine in her system. This discovery prompted a full investigation into Shipman’s practice, focusing on the deaths of other patients under his care. Investigators found that many of Shipman’s deceased patients had been cremated without post-mortem examinations, making it difficult to establish exactly how many people he had killed. However, the pattern became clear: an unusually high number of deaths occurred shortly after Shipman had visited his patients, and he had often been present at the time of death.

The police investigation eventually uncovered a pattern of behaviour that stretched back many years. Shipman was arrested in September 1998 and charged with 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery related to Kathleen Grundy’s altered will.

Trial and Conviction

Shipman’s trial began at Preston Crown Court in October 1999 and lasted until January 2000. The prosecution presented evidence of the 15 murders, which all followed a disturbingly similar pattern. The key pieces of evidence were the lethal levels of diamorphine found in the victims’ bodies, Shipman’s falsified medical records, and the forged will of Kathleen Grundy. Throughout the trial, Shipman remained calm and emotionless, showing little remorse for his actions.

The jury found Shipman guilty on all charges, and on 31st January 2000, he was sentenced to life imprisonment with a recommendation that he never be released. Justice Forbes, who presided over the trial, described Shipman’s crimes as “wicked beyond belief,” and his life sentence without the possibility of parole reflected the severity of his actions.

However, the 15 murders for which Shipman was convicted represented only a fraction of his crimes. A subsequent inquiry into his medical practice concluded that he had likely killed at least 218 patients over a 23-year period. The true number could be higher, as many of his victims had been cremated, leaving no evidence behind.

Suicide and Legacy

Harold Shipman maintained his innocence throughout his imprisonment. However, on 13th January 2004, a day before his 58th birthday, Shipman hanged himself in his prison cell at HM Prison Wakefield. His suicide deprived many of the victims’ families of the chance to see him serve out his life sentence, but it also ensured that he would never be able to harm anyone again.

Shipman’s crimes had a profound impact on the British medical community and the public at large. The trust that people placed in their doctors was deeply shaken by the realisation that a respected physician had been able to commit such horrific acts for so long without detection. As a result of the Shipman case, significant changes were made to the way doctors are monitored in the UK. The Shipman Inquiry, chaired by Dame Janet Smith, led to recommendations for better safeguards within the medical profession, particularly regarding the prescribing and monitoring of controlled substances.

One of the most significant reforms was the introduction of tighter regulations for death certifications and the creation of a national system for monitoring unusual death patterns. Additionally, doctors’ access to powerful drugs such as diamorphine was more strictly regulated, and there was increased scrutiny of general practitioners’ behaviour and decision-making processes.

Harold Shipman is remembered as one of the most prolific serial killers in recorded history, with his murders representing a grotesque abuse of power and trust. Shipman used his position as a doctor to prey on the most vulnerable members of society—elderly patients who trusted him to care for them in their final years. The scope of his crimes is almost unfathomable, and the betrayal of trust was profound. His case serves as a reminder of the potential dangers of unchecked authority, even in professions traditionally associated with care and healing.

Shipman’s legacy, while horrifying, brought about necessary reforms in the medical profession, ensuring that future abuses of power could be more easily identified and prevented. Though his actions were monstrous, the changes that followed his conviction have helped to restore some measure of safety and oversight in the healthcare system.

Fred West (and his wife, Rosemary West): House of Horrors

Frederick Walter Stephen West, born on 29th September 1941 in Much Marcle, Herefordshire, became one of Britain’s most notorious serial killers. His wife, Rosemary Pauline “Rose” West (née Letts), born in November 1953 in Northam, Devon, was his accomplice in many of these crimes. Their case shocked the nation due to the extent and nature of their crimes, which included multiple murders, sexual assaults, and the abuse of their own children.

Early Life and Background

Fred West grew up in a poor farming family with six siblings. His childhood was marked by isolation and alleged incidents of incest within the family. He left school at age 15, barely able to read or write. Early in his life, he displayed troubling behaviour, including alleged sexual assaults on young girls.

Rose West had a difficult upbringing as well. Born to Bill Letts and Daisy Fuller, she experienced an unstable childhood. Her father was known to be domineering and abusive, while her mother suffered from depression and received electroconvulsive therapy during Rose’s upbringing. Rose was described as having learning difficulties and exhibited behavioural problems in her youth.

Meeting and Relationship

Fred and Rose West met in early 1969 when Rose was just 15, and Fred was 27. Despite Fred already being married to Rena Costello and having two children, he began a relationship with Rose. By 1970, Rose had moved in with Fred and was caring for his children. Fred was imprisoned for theft later that year, and during this time, Rose is believed to have killed Fred’s stepdaughter, Charmaine.

When Fred West was released from prison in June 1971, he and Rose married. They settled at 25 Cromwell Street, Gloucester, which would later become infamous as the “House of Horrors.” The couple had eight children together, and Fred had at least two more from previous relationships.

Criminal Activities

The West’s criminal activities spanned over two decades, from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. They were involved in multiple murders, with most victims being young women. Their modus operandi typically involved abducting women, subjecting them to sexual abuse and torture, and then murdering and dismembering them. Many of the bodies were buried in the cellar or garden of their Cromwell Street home.

The couple’s children were not spared from harm. They were subjected to physical and sexual abuse, and some were involved in the abuse of other victims. The Wests also rented out rooms in their house, with some lodgers becoming victims.

Known victims included:

- Charmaine West (Fred’s stepdaughter)

- Catherine “Rena” West (Fred’s first wife)

- Lynda Gough

- Carol Ann Cooper

- Lucy Partington

- Therese Siegenthaler

- Shirley Hubbard

- Juanita Mott

- Shirley Anne Robinson

- Alison Chambers

- Heather West (Fred and Rose’s daughter)

It is believed there may have been more victims, but the exact number remains unknown.

Discovery and Arrest

The West’s crimes came to light in 1992 when Fred was accused of raping his 13-year-old daughter, and Rose was arrested for child cruelty. During the investigation, police became suspicious about the disappearance of Heather West, Fred and Rose’s eldest daughter, who had been missing since 1987.

In February 1994, police obtained a warrant to excavate the Wests’ garden at Cromwell Street. They discovered human remains, and Fred West was arrested for murder. As the investigation continued, more bodies were found both in the house and at other locations associated with Fred.

Initially, Fred West took sole responsibility for the murders, attempting to protect Rose. However, as evidence mounted, both were charged with multiple counts of murder.

Legal Proceedings

Fred West was charged with 12 murders but committed suicide in his prison cell on 1st January 1995 before his trial could begin. Rose West was charged with ten murders and stood trial at Winchester Crown Court in October 1995. She maintained her innocence throughout, but on 22nd November 1995, she was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order, meaning she will never be released.

Aftermath

The case of Fred and Rose West had a profound impact on British society and the criminal justice system. It led to discussions about child protection, the nature of evil, and the potential for seemingly ordinary people to commit horrific crimes. The house at 25 Cromwell Street was demolished in 1996 to prevent it from becoming a macabre tourist attraction.

The surviving West children have struggled with the legacy of their parents’ crimes. Some have written books or given interviews about their experiences, while others have chosen to remain out of the public eye.

Psychological Profile

Experts have debated the psychological profiles of Fred and Rose West. Fred was often described as a psychopath, showing little remorse for his actions and possessing the ability to manipulate others. His troubled childhood and possible head injuries from motorcycle accidents have been suggested as contributing factors to his behaviour.

Rose West has been described as equally dangerous, if not more so, than her husband. Psychologists have suggested she may have a severe personality disorder. Her abusive childhood and possible genetic factors have been considered in analysing her behaviour.

The case of Fred and Rose West remains one of the most notorious in British criminal history. It serves as a chilling reminder of the depths of human depravity and the complex factors that can lead to such extreme criminal behaviour. The impact of their crimes continues to resonate, serving as a subject of study for criminologists, psychologists, and sociologists seeking to understand and prevent similar atrocities in the future.

John George Haigh: The Acid Bath Murderer

John George Haigh was a British serial killer who gained notoriety for his particularly gruesome method of disposing of his victims. Haigh’s crimes shocked post-war Britain not only for their brutality but also for the calculated and systematic nature of his murders. His ability to charm and manipulate those around him allowed him to perpetrate his crimes undetected for several years. Haigh’s story is a disturbing blend of deviance, greed, and the exploitation of vulnerable individuals, all underpinned by his cold-blooded approach to murder.

Haigh was born on 24th July 1909 in Stamford, Lincolnshire, to John and Emily Haigh. His family belonged to a conservative and highly religious sect called the Plymouth Brethren, which imposed strict rules and a sense of moral superiority. Haigh’s upbringing was heavily influenced by his parents’ religious fervour, with his father instilling in him a fear of sin and punishment. His father even told Haigh that he had a “mark of Cain” on his body, a supposed physical sign of sin that would remain unless he led a virtuous life. As a result, Haigh grew up in a deeply repressive environment, often feeling isolated and misunderstood. These early experiences likely contributed to his later behaviour, as they seemed to foster a sense of detachment from the conventional morality that guided most people.

Despite his strict upbringing, Haigh was academically capable and attended Wakefield Cathedral School before working as an apprentice to a firm of motor engineers. He showed little interest in settling into an ordinary life, instead drifting from job to job, often engaging in petty crimes such as fraud and theft.

Haigh’s natural charm and quick wit enabled him to present himself as a respectable businessman, but underneath this façade lay a ruthless and calculating criminal. His early criminal activities saw him convicted multiple times for fraud during the 1930s, and he served several short prison sentences. However, his desire for wealth and status, combined with his increasing contempt for human life, led him down a far darker path.

In the 1940s, Haigh began to develop a fascination with the idea of the perfect crime, one in which the victim would simply disappear without a trace. He believed that by destroying the body, he could eliminate all evidence of murder and thus evade capture. This notion became the foundation of his future crimes. Haigh had read extensively about methods of body disposal and had come across the use of acid to dissolve organic material. It was this grisly technique that he would later employ with chilling precision.